Order now to receive by Mar 3.

45% Off Sitewide + Extra 10% Off When you Buy 2 or More

Within U.S. Only

Carefully curated by iCanvas

By Subject

Gallery-Worthy Quality, Made for You

Every piece we create starts with an artist’s vision and ends with handcrafted quality you can feel. From bold metal and glossy acrylic to classic canvas and more, our prints are built to last and made to inspire.

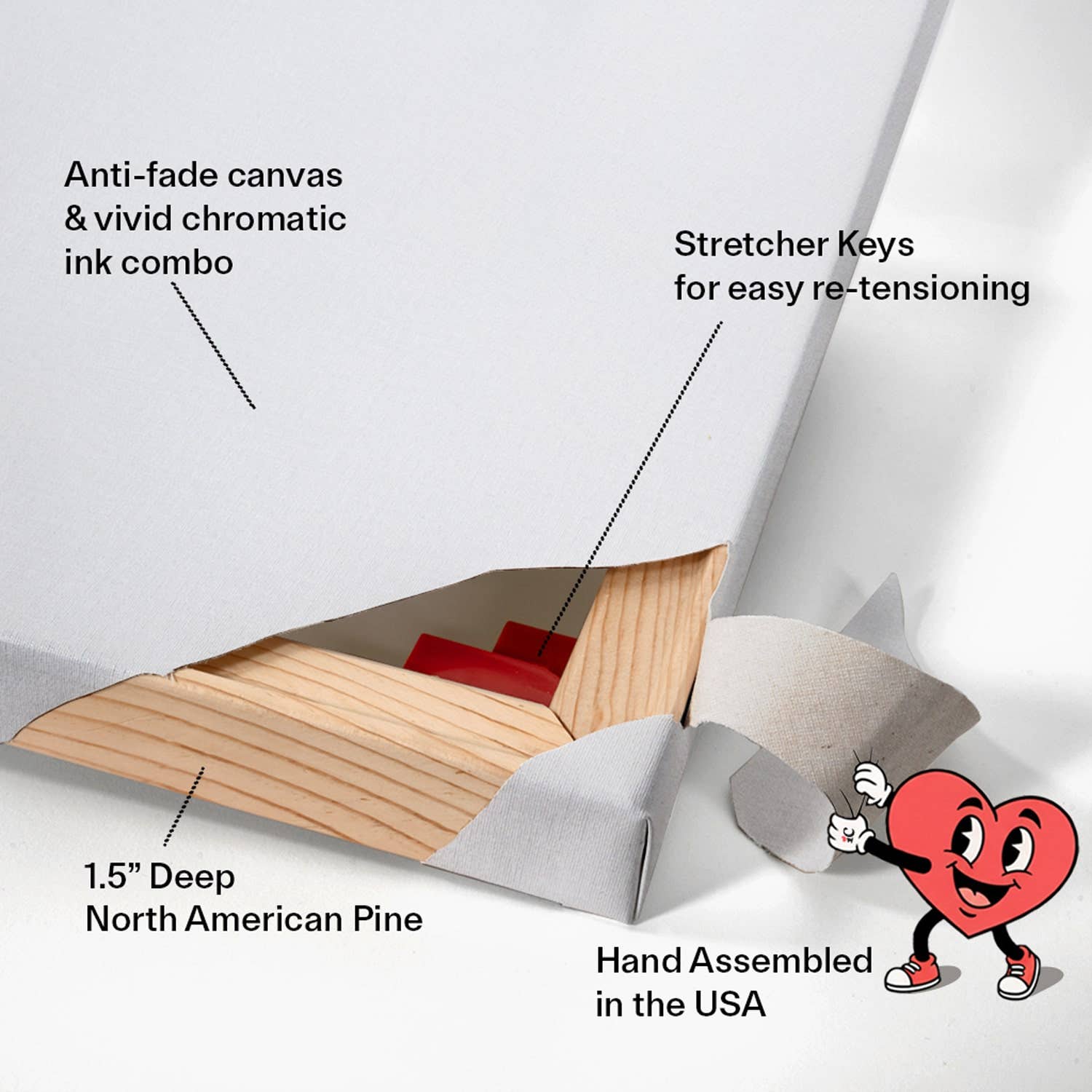

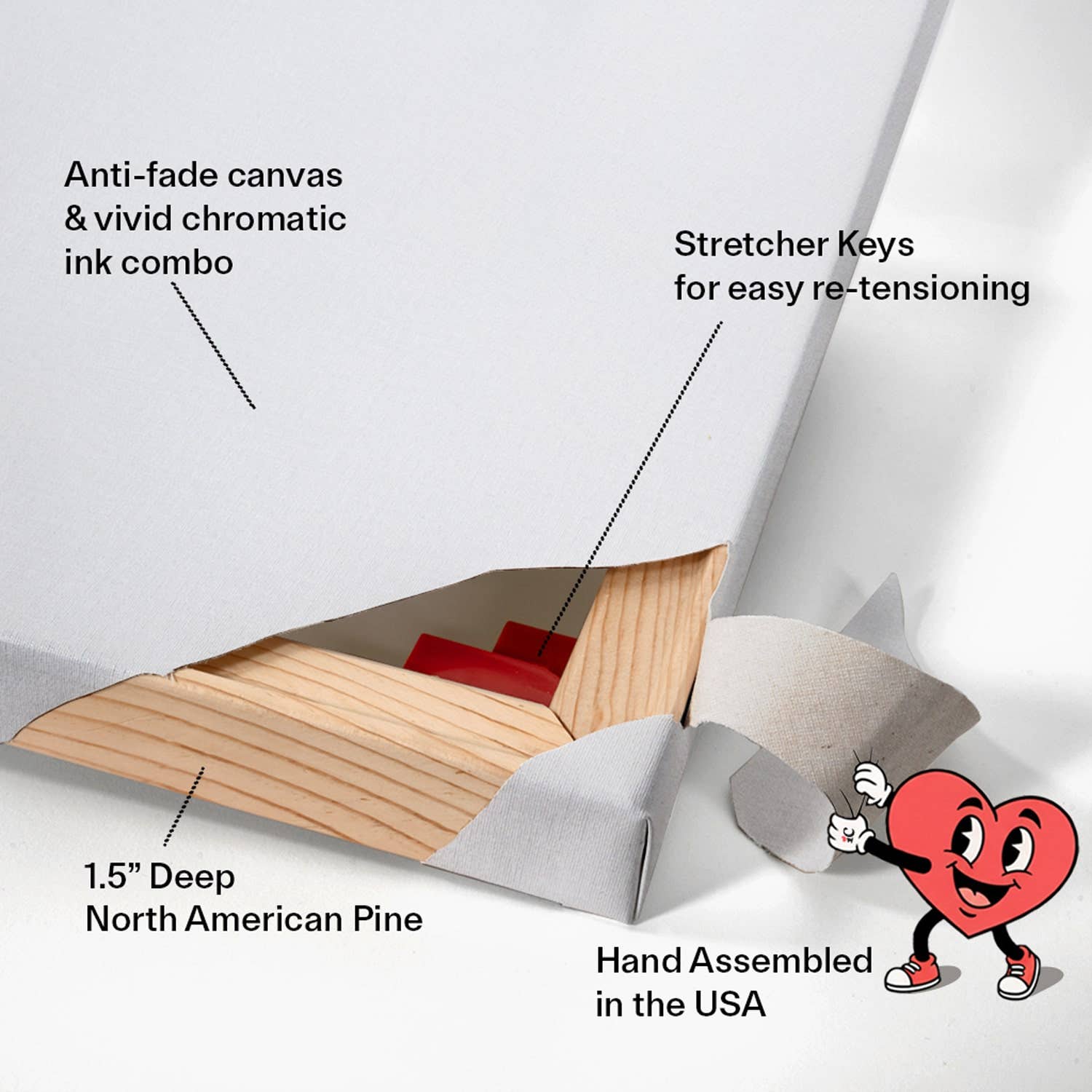

Printed on premium canvas with fade-resistant inks, our wall art captures rich textures, bold color, and stunning detail. Each piece is built for lasting impact, bringing the artist’s vision to life in your home - for years to come.

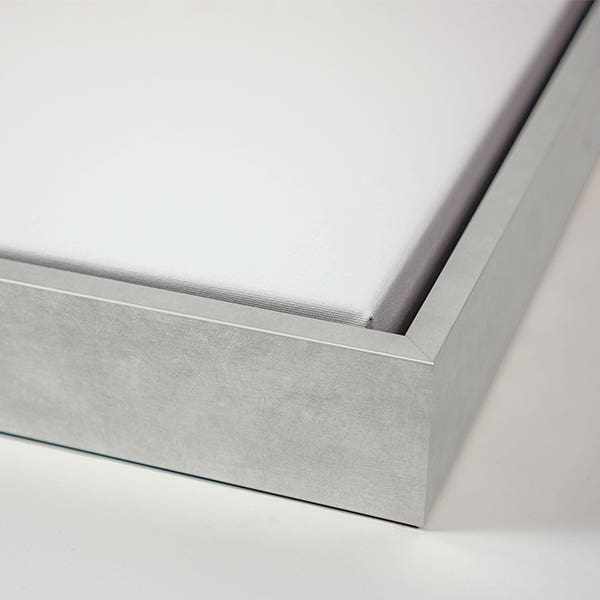

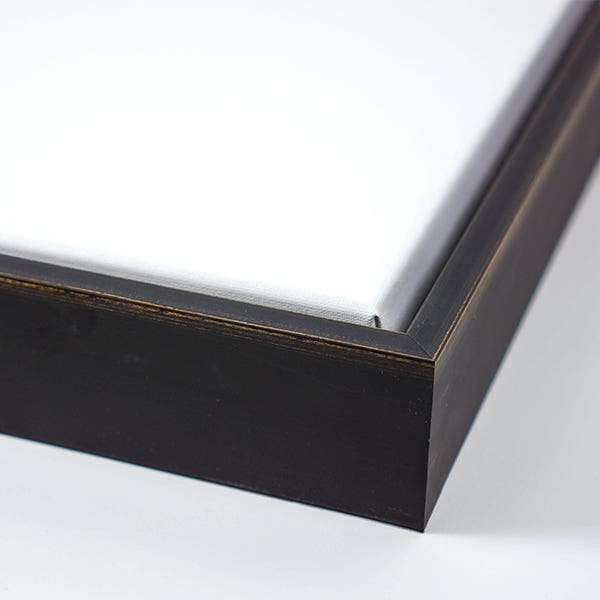

Every canvas is hand-stretched and framed with care using custom wood frames made in-house. Built for beauty and durability, our frames are more than just support - they’re a part of the artwork, elevating every piece with intention.

We believe that everyone deserves meaningful art. That’s why we offer gallery-quality pieces at prices that make it easy to decorate your space, express your style, and support working artists around the world - no compromise required.

At iCanvas, we don’t just showcase artists - we celebrate them. From bold new voices to established creators, our collection is full of expressive, soul-filled art that turns emotion into something you can see, feel, and hang on your wall.